Kubernetes changed the way companies deliver value to their customers. Changes can be rolled out in production in a matter of seconds, costs (both infrastructure and operations wise) are reduced and scalability is a consequence of the process. One of the main pillars of K8s is high availability: the possibility of running multiple copies of your service (a.k.a. pods) reduces the chances of outages and service degradation.

But is this accurate? Does K8s guarantee high availability out of the box?

Well, the answer is a vague yes and no, and I’ll explain why and how to make your services (really) high available.

But, before starting, let’s recap the definition of high availability:

High availability (HA) means creating systems that are available in the large majority of the time (99.999% of the time, or as close as possible to that). Still, in a case of failure, the system may suffer a short downtime, but for most cases, the system is resilient enough to handle failures seamlessly.

High availability in K8s

Kubernetes achieve high availability in both cluster and application architecture. By having multiple nodes composing a cluster, it provides high availability by scheduling pods in different nodes, removing the single point of failure, for example, in a case of a node crash. Also, the default deployment strategy (rolling update) replaces old instances of the service gradually, which reduces the chances of downtime during deployments. The same strategy is applied to rollbacks.

The caveats

Kubernetes is composed of many moving parts, and one of them is called kube-scheduler. It’s part of the K8s control plane and, as the name suggests, it’s responsible to schedule the pods in the nodes.

But how does the scheduler make this decision?

Kube-scheduler uses many different metrics to calculate a score for each node. In the end, the node with the highest score is selected to host the pod. The metrics used to calculate the score goes from the number of resources already present in the node, resource balance among nodes, to the number of taints and tolerations, node affinity, etc. For a full list of the metrics used in the process, refer to the Kube-scheduler official documentation.

But the point is: depending on the current state of your cluster, the placement decision made by kube-scheduler might need to sacrifice some points in favor of others, and one of these sacrificed points might be availability.

Case 1: node crash

Let’s suppose the following scenario:

You have a K8s cluster composed of 4 nodes: 1 master + 3 workers.

Since the master is tainted, it’s not feasible to host service pods, so you end up with 3 workers to host all your services. Your cluster is running and you’ve multiple services being hosted, each service with multiple pods. Suddenly, due to a hardware problem on the cloud provider, one of your workers crashes. Kube-controller-manager, the component responsible to control the desired number of pods for a deployment, identifies this crash and manages to reschedule the dead pods in the two remaining workers.

Some minutes later, a new worker is created to replace the crashed one and join the cluster. Since K8s doesn’t re-balance the cluster, the pod’s distribution remains the same, with the two initial workers holding all the pods and the new worker “idle”.

Then, a new deployment is triggered in K8s, asking for 3 pods. Again, kube-scheduler runs the scoring algorithm in all the nodes and select the ones with the highest score to host the pods.

And here is where the problem starts: since you’ve two workers with multiple pods and one worker empty, this empty worker will get a higher score compared to the others due to resource balance. And then, all your three pods land the very same worker.

Minutes later, another hardware failure on the cloud provider (busy day, hum?!) and the fresh new worker, created minutes ago, crashes too.

And then I asked you: what happens with your service?

Turns out that, until kube-controller-manager manages to reschedule the 3 pods in the two remaining workers, your service is down.

Let’s see this in practice:

I’ll create a four-nodes K8s cluster, as described in the scenario above, in my localhost, using Kind (if you don’t know what Kind is, I recommend you to check my last blog post, clicking here).

The Kind config file is the following:

apiVersion: kind.sigs.k8s.io/v1alpha3

nodes:

- role: control-plane

- role: worker

- role: worker

- role: worker

And then we create the cluster:

Now, let’s trick K8s and make the workers kind-worker and kind-worker2 really busy, while keeping the third one (kind-worker3) idle: we’re going to deploy 20 busy pods in each worker using a node-selector to force pods being placed in the specific workers.

So, for placing 20 pods on kind-worker:

$ cat > deploy-1.yaml <<EOF

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: busypod-1

name: busypod-1

spec:

replicas: 20

selector:

matchLabels:

app: busypod-1

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: busypod-1

spec:

containers:

- name: busypod-1

image: busybox:1.31.0

command: ["sleep", "86400"] # 24 hours

nodeName: "kind-worker"

EOF

$ kubectl apply -f deploy-1.yaml

… and another 20 pods on kind-worker2:

$ cat > deploy-2.yaml <<EOF

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: busypod-2

name: busypod-2

spec:

replicas: 20

selector:

matchLabels:

app: busypod-2

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: busypod-2

spec:

containers:

- name: busypod-2

image: busybox:1.31.0

command: ["sleep", "86400"] # 24 hours

nodeName: kind-worker2

EOF

$ kubectl apply -f deploy-2.yaml

The result is the following:

Now, let’s deploy our service (hello-world). This service asks for 3 pods and won’t have any node selector, leaving to kube-scheduler freely decide the best place to host our 3 pods:

$ cat > deploy-3.yaml <<EOF

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

name: hello-world

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

spec:

containers:

- image: dockercloud/hello-world

name: hello-world

ports:

- containerPort: 80

EOF

$ kubectl apply -f deploy-3.yaml

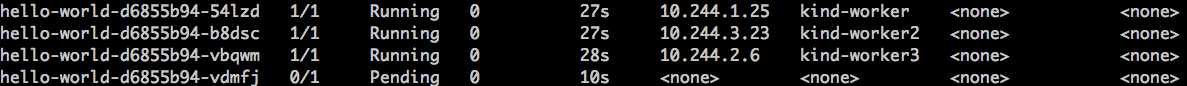

Now let’s check the pod’s placement for our service:

As described initially, all the three pods were scheduled on the third worker (kind-worker3), since it’s idle compared to the other two. So, if the third worker crashes, our service is offline for the time taken to reschedule the pods in other workers.

How to fix it?

If high availability is the most important factor for your service, you can leverage pod anti-affinity.

Pod anti-affinity is a set of rules accepted by K8s that constraints which nodes are eligible to accept a pod, based on other pods placement. In other words, with pod anti-affinity, you can specify rules such as:

This pod should run on this node only if no other pod of the same type is already running here.

There are two types of rules for pod anti-affinity:

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution: the rule will try to be satisfied, but in case no solution is found, the pod is free to be scheduled anywhere;requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution: the rule must be respected to place the pod. In case no solution is found, the pod remains in thependingstate;

So, applying pod anti-affinity on our hello-world service, the manifest becomes:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

name: hello-world

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

spec:

containers:

- image: dockercloud/hello-world

name: hello-world

ports:

- containerPort: 80

affinity:

podAntiAffinity:

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 100

podAffinityTerm:

labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

topologyKey: kubernetes.io/hostname

The anti-affinity rule above tries to place pods of hello-world on nodes that don’t have a pod of the same type already running. The concept of same type is defined by the labels assigned to the pod. In our case, pods are considered of the same type if they all have the label app=hello-world.

Finally, pod anti-affinity requires a topologyKey parameter. This parameter is used to identify similar nodes in the cluster. In our case, we’re using kubernetes.io/hostname, which means that nodes with different hostnames are considered different nodes, but you can go further: if you want to spread your pods on different availability zones, for example, you can label your nodes with az=eu-central-1a, az=eu-central-1b, etc, and change the topologyKey to az.

So, after applying the updated manifest to our service, let’s check the placement of our pods:

Now our pods are spread among distinct nodes in the cluster.

In our example, we’ve used a preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution rule, which means kube-scheduler will try its best to respect the rule, but if no solution is found, the pods are free to be placed anywhere, including all on the same node.

You can, however, force your pods to be placed in different nodes, by replacing the rule to requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution. In our example, the deployment manifest would be:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

name: hello-world

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: hello-world

spec:

containers:

- image: dockercloud/hello-world

name: hello-world

ports:

- containerPort: 80

affinity:

podAntiAffinity:

requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

topologyKey: kubernetes.io/hostname

But pay attention that, if no node can host the pod, it remains on the pending state until a suitable node becomes available. We can easily see this by scaling up our deployment to four pods. In this case, the first 3 pods will be scheduled, each one on a different node, while the forth pod will remain on pending state since no node is capable of host it without breaking the pod anti-affinity rule:

Case 2: Voluntary disruption

One of the principles of K8s is to treat your pods, not like pets, but cattle. This analogy tells us that resources in K8s are ephemeral, and creating, deleting and replacing them is a normal operation on the cluster.

Kubernetes defines this behavior as disruptions, and they can be classified into two groups:

- Voluntary disruptions: disruptions performed due to normal cluster operation, such as rolling out a new version of your system, draining a node for maintenance, etc.

- Involuntary disruptions: disruptions performed due to unexpected behaviors, such as hardware failure, kernel panic, etc.

Let’s focus on voluntary disruptions.

Let’s go back to our initial scenario, where we’ve all the three pods of hello-world service scheduled in different nodes using pod anti-affinity. Hardware failures are rare events, especially for big cloud providers, so you might argue that the chances of the node crashing are low, and I kind of agree. However, there’s something more common that can make a node offline: maintenance.

Operations team needs to perform maintenance on the K8s cluster frequently, like updating the K8s version, installing patches or even moving an instance to newer generation hardware. In this process, the technician needs to take the node out of the K8s cluster, similar to what would happen during a hardware crash.

Does he/she just unplug the node, out of nothing?

Of course not! The process requires removing all the pods from the node in a controlled manner before taking the instance off, an operation called node drain. Draining a node kills the pods in the node and wait until they’re rescheduled in other nodes.

But how do you guarantee that you have a minimum number of pods serving your app? Imagine that you’re in the middle of deployment of our service and one of your pods is out due to the normal rollout operation. At the same time, the Ops team is draining another node for maintenance, and another pod is gone. Finally, the node serving your last pod crashes. Guess what? Your service is offline again.

Except for the node crash, all other disruptions are voluntary, and shouldn’t put your service in an unstable situation. There must be a way to say to K8s:

OK, I’ve no control over involuntary disruptions, but for voluntary ones, I want to have at least a minimum number of pods running my service, otherwise, the voluntary disruption mustn’t happen.

Indeed there is a way, and it’s called PodDisruptionBudget.

PodDisruptionBudget (PDB) limits the number of pods that can be taken down from your service during voluntary disruptions. You can set up your PDB to always have two pods of your service running, so in case of a node crashes, you still have one pod serving it, and you increase the availability of your service. If PDB is respected by the tool used during the voluntary disruption (for example, kubectl drain respects PDBs), the operation is blocked if the disruption will violate one or more PDBs defined in your cluster.

Let’s see how to setup a PDB:

apiVersion: policy/v1beta1

kind: PodDisruptionBudget

metadata:

name: hello-world-pdb

spec:

minAvailable: 2

selector:

matchLabels:

app: hello-world

The PDB above demands that at least 2 pods (minAvailable: 2) with the label app:hello-world are always running in your cluster. In this case, if there are exactly 2 pods running of this type and a node drain is triggered, it must wait until a third pod is restored in your service for the operation to proceed.

You can also use the opposite logic: instead of specifying the minimum number of available pods, you can specify the maximum number of unavailable pods, using maxUnavailable: 2. In this case, doesn’t matter how many pods are running for your service, your PDB allows that at most 2 can be taken off during voluntary disruptions.

Conclusion

Kubernetes, undeniably, helps teams to create more robust and available services, but depending on the scenario, it needs to make some hard decisions to guarantee a smooth operation of the cluster.

There’s no way to K8s know exactly which points are crucial for your application. So, some times, you might need to dig a little deeper and help the scheduler to make good decisions, according to your service requirements, and pod affinity, anti-affinity, and PDB can be of great help to give these hints to the scheduler.

Further reading: